JP Morgan Chase thought it owned 54 metric tonnes of nickel, sitting in bags in a warehouse in Rotterdam.

Instead, it turns out that the bags contained nothing more than shiny rocks.

JP Morgan Chase thought it owned 54 metric tonnes of nickel, the most highly valued base metal. The bank had reason to believe this nickel was stored in bags at a warehouse in Rotterdam. It turns out these bags are, instead, full of stones. Ben and Aimee discuss the case of JP Morgan's missing nickel and how this story is just the latest drama in the nickel trade.

To understand why JP Morgan needs to own bags of rocks in a warehouse in Europe's largest port, we talked to Dan Davies, the author of Lying for Money, about the specifics of this scandal and, as he put it, "the general history of putting fake s**t in warehouses."

Here's a lightly edited transcript of our chat.

What happened here?

When people trade nickel futures, there has to be the option of physical delivery in order to make sure that the price of the futures contract is tied down to the physical price of the metal. But equally, you don't want every futures trader to have to run a warehouse or be in a position to accept delivery of tons of metal. So the way the contract works is that you trade warehouse receipts, and the futures exchange allows you to settle by transferring ownership of a load of nickel metal that is held in one of a bunch of approved warehouses, and effectively they don't even move it from place to place within the warehouse. They just kind of changed their record of who owns which containers of ingots, or however they store them.

And even that – moving around warehouse receipts– that’s pretty rare, because most of these things are cashed out and just settled.

Absolutely. It's just there in order to make sure that there is a link to the physical metal because the nickel futures market is one in which unlike some of the other more speculative futures markets, there is pretty big participation by people who actually wants to trade the price of nickel because they want the metal.

The important thing is as you said, that this nickel that's in the warehouses for the purposes of futures trading, never really leaves those warehouses. It doesn't even actually change ownership very often, because they settle the contracts in cash.

And in this case, what people thought were bags of nickel were just bags of rocks.

Exactly. It's a classic warehouse receipt fraud of the sort that has been going basically for as long as warehouse receipts have been treated as financial instruments that could be the subject of futures contracts or loan financing.

Okay, so, you’re the expert on this particular fraud. What's the basic outline of how this warehouse receipt fraud works? In this case, they don’t yet seemed to have pinned if it was fraud or something else–

We don't know who did it, but when you’ve got a container full of rocks where a valuable metal ought to be, you've got to guess it didn't happen purely by mistake.

Fair enough. Take us through the basics of this kind of category of fraud.

It's a classic example of a situation in which they've decided to use trust, rather than verification. Because the whole financial system works on the basis of trust. If you have to verify everything, then you'd never get anything done. You'd spend your whole life checking things. In this case, rather than having someone constantly checking the metal, moving heavy metal around on trucks and everyone taking delivery of it, they decided that warehouse receipts were as good as the physical thing.

This is something that's been going on for ages. It's always been the case that when you borrow money collateralized against goods, do very rarely take the goods down to your bank so that the goods are stored in their vaults. In fact, the only situation in which I know that happens is that there's an Italian bank, which has a special cheese ripening facility so that Italian producers of parmesan cheese can borrow money against their cheese while it's maturing.

Most of the time, the stuff is either held in a special bonded warehouse, or it's held on the customer's premises. Someone inspects it and issues a warehouse receipt. And then for financial purposes, that warehouse receipt is the goods you can borrow against it as if it was collateral.

You can trade futures on it as if it was delivery of physical metal. What it is, is a certificate that someone has inspected that and confirmed your ownership of the goods and in the financial system that's as good as having the physical things.

So, someone comes into the system and says “ah, this makes sense. I can borrow against this thing. But what if this thing never existed? I could just borrow money for free.”

Absolutely. The warehouse receipt system is a circle of trust. And once you're in that circle of trust, no one checks up on it again. That would be a crazy thing to do. It would be like getting a set of audited accounts and then going to the company and doing another audit yourself. That's not what it's for.

This is a much easier way of stealing a load of nickel than stealing the physical nickel would be. If you've managed to issue a misleading warehouse receipt, then you can be pretty sure that it will be a long time before anyone checks up and finds out whether that corresponds to a physical assets because the whole purpose of the system of receipts is meant to prevent everyone from having to do that check every time they extend credit or every time they trade futures.

What are some other examples this kind of a fraud?

This kind of fraud is absolutely endemic. There's one or two every year. A couple of years ago, a load of banks ended up getting out of the financing of shipping fuel because they had been caught by a version of this scam so hard.

In the industry jargon, you tend to refer to this as a salad oil scam. And they call it a salad oil scam after the great salad oil fraud of the 1960s, which was where a larger than life character called Tino De Angelis was the biggest single trader of soybean oil. And he financed himself through warehouse receipts – American Express company's financing subsidiary would lend him money against the receipts. These were warehouse receipts from a warehousing facility for soybean oil which Tino controlled, because soybean oil has to be stored in specialist facilities. It can't just be put into any warehouse. And what Tino realized is that oil floats on water. And so when the inspector from his bank came around to check that the warehouse receipt was accurate, you can't necessarily tell the difference – particularly in winter when things freeze up – between a tank full of valuable salad grade soybean oil, and a tank that's basically full of seawater with a few gallons of soybean oil floating on the top.

It was crazy. In the end, he had warehouse receipts outstanding which if you ever sat down and added them up, would account for more soybean oil that was produced in the entire United States of America in that year.

And sooner or later, he got into futures trading. He went extravagantly bankrupt and the bank went down to the warehouse facility to take possession of their collateral and they found a load of fake tanks full of seawater. It was a huge financial loss in the time. It happened on the weekend that Kennedy was assassinated, so it didn't make quite as big headlines as it should have done. But it basically brought down a number of commodities brokerages that had extended too much credit to this guy on the basis of warehouse receipts which did not reflect physical commodities.

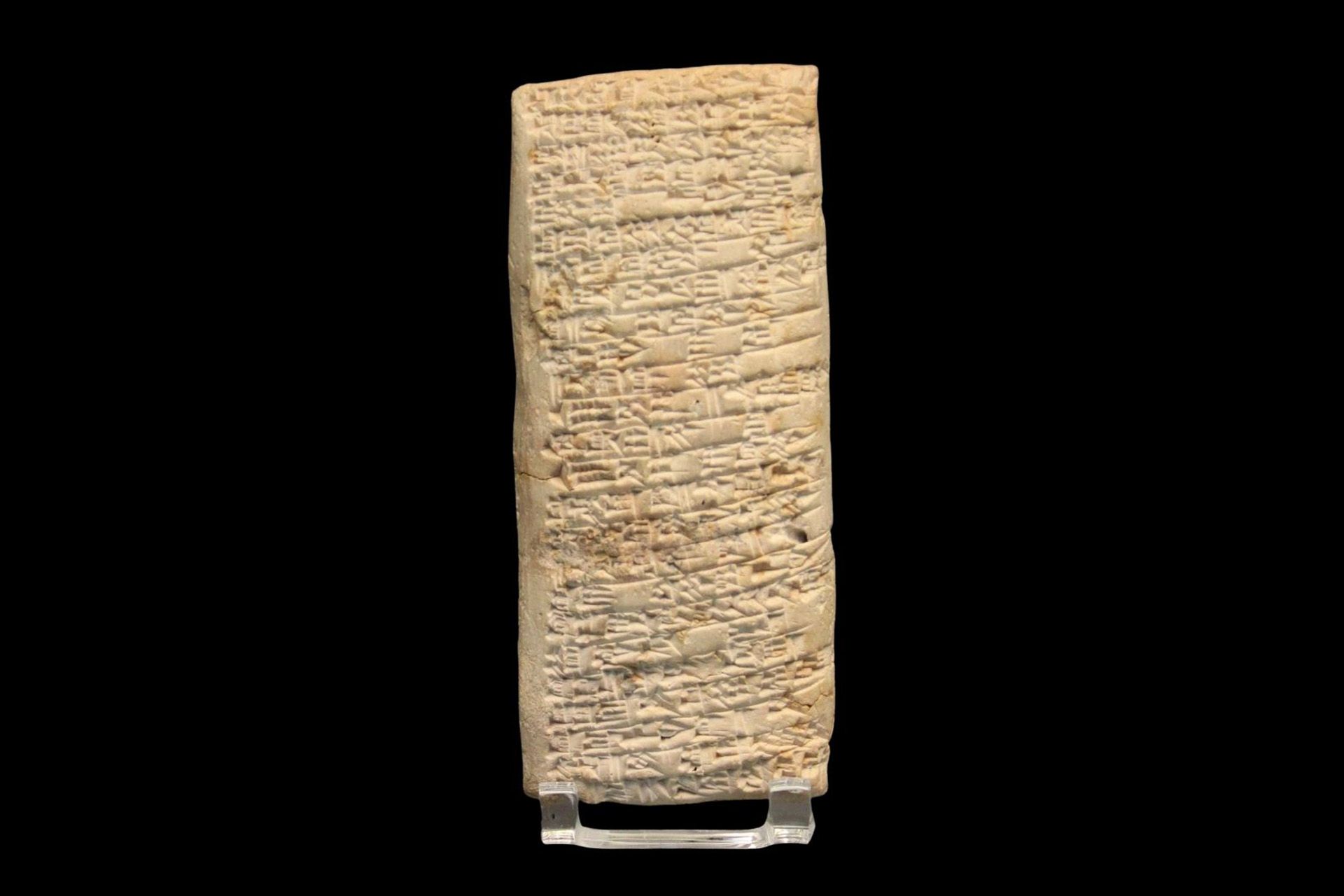

There's a case that’s documented on a tablet from ancient Mesopotamia where this trader is upset because he bought copper ingots and they turned out to be junk and he wants his money back.

Absolutely. The original eureka moment was when Archimedes jumped out of his bathtub, realizing that the displacement of water would allow him to discover who had been adulterating gold coinage.

These kinds of things go right the way back through history, because as soon as you've invented a system in which people assign value to things, you've invented a system in which people can be fraudulently misled into assigning values to things that don't actually have the value that they want.